updated input

Input week of September 9, 2019

“100 Things About Writing A Novel” by Alexander Chee (Yale Review)

“What 100 People, Real and Fake, Believe about Dolores” by Ben Greeman, [McSweeneys, 10/20/2000]

An Interview with Peter Doig, by Joush Jelly-Schapiro, [The Believer Mag, 3/1/2012]

Doig’s FilmClub

The harder they come

Whether French film-makers (Renoir and others) would have been painters if born 50 years earlier or Internet designers if 50 years later

The Ends of Art according to Beuys, by Eric Michaud/Rosalind Krauss , [October, Vol. 45 (Summer 1988]

Beuys is a voice and intended to overcome the silence of Duchamp

E.g.

The disturbing element in Beuys’s work is not to be found in his drawings, which have their place in public and private collections throughout the world, nor his “performances,” which have their place within the Fluxus movement and within a general investigation of the limits of art. It lies rather, I believe, in the flood of pronouncements testifying to the privilege that he gave, throughout his lifetime, to spoken over plastic language. It is this constant inundation of his ‘works’ by words – both his own and those of others – this frantic proselytizing in which he exhausted himself up to the time of his death. But it is also – and in the very same impulse that led him to repeat what he thought was Christ’s teaching – this constant wish to ‘clarify the task that the Germans have to accomplish in this world,’ this insistence on the ‘duty of the German people,’ above all to deploy this ‘resurrective force’ tha t was to lead to the transformation of the social body by man-turned-artist.

October, at 38-39.

Other themes:

Duchamp is counterproductive because he shows that all objects can be art, but failed to go further and show that all humans are necessarily artists

Beuys’s notion of Gestaltung – the putting into form – is an end, and it will, he claims, “bring about the resurrection of meaning that Duchamp’s silence had buried.”

But the close of the essay shows inherent problems with Beuys Gestaltung and notion of Germany as place to revivify Christianity: if each person is an artist by virtue of the social activity – the putting into form –, then collectively a culture is engaging in the productive and transformative task of social sculpture. Of creating a new form of life. And the risk is that the end of achieving Gestaltung will make (other) people means – that it becomes a feedback loop of subjugation in which real mean and the real world, which become reduced to be the mere instruments of its exercise, mere putty in the work of social sculpture. Which, it being Germany and all, should be cause for concern.

Aside: Beuys founded the Green Party in Germany, if that is a mitigating weight on the totalizing talk of Germanic “duty” and “self-becoming” (and it might not be).

“What Makes Indians Laugh” Surrealism, Ritual, and Return in StevenPazzie and Joseph Beuys by Claudia Mesch, [Journal of Surrealism and the Americas 6:1(2012)]

A View Beyond the Personal by Ange Mlinko, NY Review of Books, 5/23/2019 [Review of John Koethe’s Walking Backwards: Poems 1966-2016]

HMS Bounty by Rachel Kushner, Yale Review (January 2018)

It’s said that capitalism relies on a system of selling something you don’t own to someone who doesn’t want it. Which is identical to how a Lacanian defines love. The lover makes a gift of his banality as if it were a wonder. He pretends to offer something more than his banality, a piece of the world that reflects his love and that he does not, in reality, possess. In both cases, love and futures, you force something you don’t own onto someone who does not want it.

Capital requires the confidence that you can do business with time. Alan Badiou says the revolution to come seems impossible only if you swallow the lie that the present is not. Once you see how impossible life already is, then the possibility of a real true actual emancipatory horizon comes into view. Got it?

[ . . . .]

In the Doge’s Palace in Venice there is a room that was once the largest indoor gathering place in all of Europe. Capacity was two thousand important men. The doges ruled Venice for six hundred years. There were 120 of them. The term of service was life. Around the upper edges of this grand salon, on all four walls, are painted portraits of all the doges. All the doges, that is, but one, a single Venetian doge who is represented by no portrait but instead a black banner, and under the banner text in Latin that reads, Here is the space reserved for Marino Faliero, decapitated for crimes.

Faliero was doge for only one year. One year of six hundred. One doge of 120. And yet: anyone who has ever been in the great salon of Venice, once the largest gathering indoor space in all of Europe; in fact, anyone asked to name a Venetian doge, a single one, any doge, will name Marino Faliero. Or at the very least, a person, when asked, will say, “The one whose memory they tried to erase. That’s the one I recall.”

[I have been in this big room, twice, and I remember the black banner, but not the man who – having been subject to erasure – became infamous and known]

Philosopher-Poets: John Koethe and Kevin Hart by Paul Kane [Raritan, Summer 2001]

Koethe’s poems typically chronicle what it is like to be experiencing life the way he does, rather than presenting the events themselves, which remain offstage and largely unavailable to us as readers. There is an intimate distancing at work whereby we get to know the poet’s experience without ever getting to know what happens to him. This makes Koethe a poet of the ambiguous antecedent . . . .

From ON BALANCE BY ADAM PHILLIPS:

The Authenticity Issue (114-15)

In her memoir Room for Doubt, the American writer Wendy Lesser has a chapter about living in Berlin; and her sense of what contemporary Berlin is like prompts invidious comparison with New York. There is, she has a sense, a “richly reflected innocence” about contemporary Berlin,

a zeal for the new that is both premised on appreciation of and wariness about the old. We have nothing like it in America. Every fw years New York ( and then the rest of the country) goes into a tortured soul-search and decides that we are all too ironic, that irony must now be thrown out so that something more – more what? more childlike? more authentic? more credulous? – something fresher and newer, at any rate, can be ushered in. But you cannot will such reforms.

The antidote for irony, and its sppposedly enerveating effect is, in Lesser’s telling list, something more childlike, more authentic, more credulous; reminiscent of Clare, and Banville in a different way, when the word ‘authenticity’ is used, it conveys something about immediacy. Irony is, as we say, a distance regulator and there is something that we nostalgic Romantics feel estranged from and want to get back to or closer to: the childlike, the authentic, states of credulity. The authentic in this list represents the retreat of skepticism, doubt, even reflection. It is trustworthy, and we can entrust ourselves to it. It allows us to yield rather than requiring our vigilance. If we can be more childlike, authentic and credulous, it is assumed, something fresher and newer can be ushered in, as though irony is our defense against the new, a kind of character armour, and if we could shrug it off, we could be more vulnerable, more receptive, capable of exchange and not ambitious for insulation.

READING, AND UNCLEAR IF I AM CONFUSED BY IT:

Form Follows Flow: A Material-driven Computational Workflow for Digital Fabrication of Large-Scale Hierarchically Structured Objects, by Laia Mogas-Soldevila, Jorge Duro-Royo, Neri Oxman

Design for the Modern Prometheus: Towards an Integrated Biodesign Workflow by Sunanda Sharma (M.S. Thesis, MIT, Media Arts and Sciences)

DORMANT READING

Whistler, life for art’s sake, Daniel Sutherland (no progress made at all)The Silk Roads, Peter Frankopan (no progress made at all)Zen and Japanese Culture, D.T. Suzuki [Purchased Kawaza Museum in Oct. 2018, been “reading” Since then]Swann’s Way (Davis) (no progress made at all). . . . . more . . . OR . . . . i suppose, less, worse, what have you.

Omens and Omelettes

Ulysses was censored. That is so 20th Century.

Lonely City (O Lang) - Redux #3, Art's Integrating Function

Lang again:

It’s a funny business, threading things together, tying them and patching them with cotton or string. Practical, but also symbolic, a work of the hands and the psyche itself. One of the most thoughtful accounts of the meanings contained in activities of this kind is provided by psychoanalyst and pediatrician D.W. Winnicott, an heir to the work of Melanie Klein. Winnicott began his psychoanalytic career treating evacuee children during the Second World War. He worked lifelong on attachment and separation, developing along the way the concept of the transitional object, of holding, and of false and real selves, and how they develop in response to environments of danger of safety.

In Playing and Reality, he describes the case of a small boy whose mother repeatedly left him to go into hospital, first to have his baby sister and then to receive treatment for depression. In the wake of these experiences, the boy became obsessed with string, using it to tie the furniture in the house together, knotting tables to chairs, yoking cushions to the fireplace. On one alarming occasion, he even tied a string around the neck of his infant sister.

Winnicott thought these actions were not, as the parents feared, random, naughty, or insane, but rather declarative, a way of communicating something inadmissible in language period. He thought that what the boy was trying to express was both a terror of separation and his desire to regain the contact he experienced as imperiled, maybe lost for good. “String,” Winnicott wrote, “can be looked upon as an extension of all other techniques of communication. String joins, just as it also helps in the wrapping up of objects and in the holding of unintegrated material. In this respect string has a symbolic meaning for everyone,” adding warningly, “an exaggeration of the use of string can easily belong to the beginning of a sense of insecurity or the idea of a lack of communication.”

The fear of separation is a central tenet of winnicott's work. Primarily an infantile experience, it is a horror that lives on in the older child and the adult, returning forcibly in circumstances of vulnerability or isolation. At its most extreme, the state gives rise to the cataclysmic feelings he called fruits of privation, which include:

1. going to pieces

2. falling forever

3. complete isolation because of there being no means for communication

4. Disunion of psyche and Soma.

This list reports from the heart of loneliness, its central court. Falling apart, falling forever, never resuming vitality, becoming locked in perpetuity into the cell of solitary confinement, in which a sense of reality, of boundedness, is rapidly eroded: these are the consequence of separation, its bitter fruit.

What the infant desires in these scenes of abandonment is to be held, to be contained, to be soothed by the rhythms of the breath, the pumping heart, to be received back through the good mirror of the mother’s smiling face.

As for the older child comma or the adult who is in adequately nurtured or has been cast backwards by loss into a primal experience of separation, these feelings often spark a need for transitional objects, cathected with love, things that can help the self to gather and regroup.

[ . . . ]

According to Winnicott, this kind of activity – [playing with string] – could do more than simply deny separation or displace feeling. The use of transitional objects like string would also be a way of acknowledging damage and healing wounds, binding up the self so that contact could be renewed. Art Winnicott thought, was a place in which this kind of labor might be attempted, where one could move freely between integration and disintegration, doing the work of mending, the work of grief, preparing oneself for the dangerous, lovely business of intimacy.

INPUT RE: 9/1-9/8, 2019

Read or finished:

33 Artists in 3 Acts by Sarah ThorntonThe Lonely City by Olivia LaingJohn Currin articles:a. John Currin, Painting’s Male Provocateur, Turns his Brush to Men [GQ Sept 2019]

b. Irresistible, by Peter Schjeldahl [12/7/2003, New Yorker]

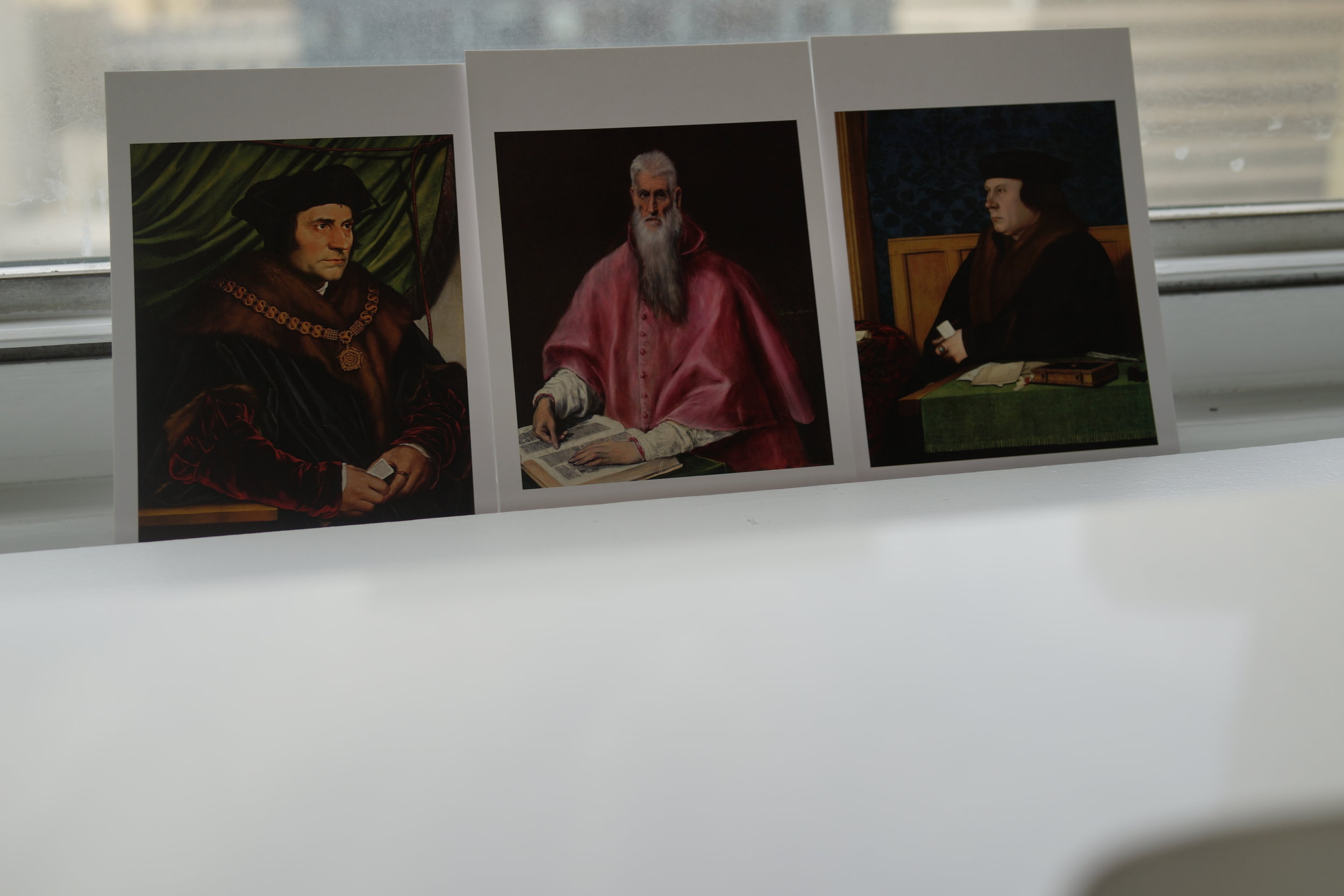

I assumed that Currin’s skilled, sly, ineffably old-fashioned work—pastiches of Old Masters and hack illustration, in easel paintings fit for a bygone Beaux-Arts salon—would remain a renegade taste, marginal to video, photography, installations, and other dominant, paint-allergic modes of contemporary art.

But to resist Currin’s claim to preëminence in art’s present state and near-future course suddenly seems beyond anyone’s ability.

[. . . .]

You wouldn’t think that resourceful, unremitting, honed offensiveness would be a winning artistic strategy. By rights, Currin’s radical conservatism ought to disgust art-world cognoscenti, and conservatives should abhor his poisoned-sugar erotica. So what’s up?

I hazard that in Currin’s art manifold pleasure disarms revulsion—without eliminating it. He demonstrates the power of the aesthetic to overrule our normal taste, morality, and intellectual convictions.

[. . . . /close of article/]

He announces a situation in which artists, wielding art, trump critics who enforce ideas. If his paintings are to be effectively countered, it must be by other, newer, better paintings.

c. Lifting the Veil by Calvin Tompkins [New Yorker profile 1/21/2008]

[the lede]

The painting shows three young women standing close together in a room. The woman in the middle faces us directly, head held high; her dress is falling open, and her bra has been pulled down to expose both breasts. On either side of her, the other two—one nude, one wearing a chic cocktail dress unzipped in back—touch her erotically. The canvas is eighty-eight inches high by sixty-eight wide. It has the scale and pyramidal structure of a Renaissance altarpiece, but, according to John Currin, who began work on it four days ago, the immediate source was an Internet porn site. What struck him about the image, he explains, was “this completely archaic pose, like the three witches or something. I think of them as Danish, because of the thinning blond hair and the gaps between the teeth. They’re not pretty enough to be Swedes. Oh, and I want to do a still-life down there in the lower right corner. I don’t really know where this picture is going yet, but I think it’s going to work.”

[ . . . . /A complication; rising action/]

A reason presented itself soon enough, in the headlines about riots in the Islamic world over twelve Danish newspaper cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad. “The response to that totally shocked me,” Currin said at dinner that night. “That the Times decided that it was not going to show the cartoons—O.K., they’re terrible-ass cartoons from a quality standpoint, but the idea that those thugs get offended and we just acquiesce, that was the most astonishing display of cowardice. And also the killing of Theo van Gogh, the film director, by some jihadist in Amsterdam—all of a sudden the most liberal societies in the world were having intimidation murders happen. That’s when it occurred to me that we might lose this thing—not the Iraq war but the larger struggle.” When I asked how this tied into his making pornographic paintings, Currin talked about low birth rates in Europe, and people having sex without having babies, and pornography as a kind of elegy to liberal culture, at which point I lost the thread. “I know how right wing this sounds,” I recall him saying, “but I was thinking how pornography could be a superstitious offering to the gods of a dying race.”

[. . . ./ the closing grafs/]

A week before Christmas, the painting suddenly came together. The body of the right-hand figure, indistinct until now, looked fully three-dimensional, with luscious flesh tones and a sensuous play of light and shadow on her belly. Currin had sketched in grisaille a still-life of bone-china cups and plates at the lower right, and he had turned the bed behind the three figures into a distinct presence, with a rumpled sheet and a curvy leg copied from his and Rachel’s flamboyantly rococo bed at home. Right now, he planned to concentrate on the three figures. “There’s not enough depth in them,” he said. The painting, he said, would not be in his upcoming show in London. Larry Gagosian had told me earlier that he would like to have this one himself—something dealers are inclined to say when they want to establish a record price.

Currin had agreed sometime earlier, rather reluctantly, to let me watch him paint, but somehow this had not happened. Today it did. He set up a palette, choosing three tubes of Robert Doak oil paint from a worktable piled high with several dozen others, and squeezing out small dollops from each. The colors were yellow ochre, vermillion, and Turkey umber, which registers as blackish green. From a lineup of liquid mediums in glass bottles, each of which had a different consistency and drying time, he selected a mixture of stand oil and balsam and poured a little of it into a small cup that was affixed to the palette. “And here’s the white I’m so excited about,” he said, squeezing from a larger tube of lead white. He went to work right away, dabbing a rather large bristle brush first into the white, and then the umber and the other two colors, mixing them quickly with a little of the oil medium on the palette, remixing until he had the brownish tone he was after, and then applying it to the leg of the central figure with quick, deft strokes. He walked back ten or twelve paces, looking, then added more vermillion and went over the section again, making it darker at the outside edge of the leg and lighter toward the middle.

I was surprised to see how fast he worked. After about ten minutes, the brownish pigment, applied over the white ground, had made its magical transition into live flesh. “I have about an hour before it gets sticky and becomes unworkable,” he explained. Now and then, he used his index finger to blur or blend the paint. “Say I want a sort of purply knee, slightly bruised or something,” he said. “I go in with black and red, maybe a little yellow.” He did so. He switched to a sable brush, much softer than the one he had been using, to work around the knee. “It starts to multiply, the grading of tones, until it becomes thousands of tones,” he reflected. “Some are accidental and some are intentional. It’s great when the accidental becomes indistinguishable from the intentional. That’s when it begins to seem like a living thing.” Watching him, it occurred to me that every brushstroke, every gradation in tone reflected a body of knowledge and a capacity for intuitive decisions that reached backward and forward in time. Also, that the art of figurative painting, which has been around for twenty thousand years or so, retains enough challenges to keep us enthralled for an additional millennium or two.

Currin stood back to look at what he’d done, then picked up a soft cloth and began wiping it off. The central figure’s legs, he said, would eventually be sheathed in green stockings. He had just been showing me how he worked.

The demonstration made me think of three other things he had said during our talks:

“The meaning of the painting is what you do with your hands.”

“The way things are painted trumps everything else.”

“So much art now doesn’t want to look like art, but painting can’t help it.”

The artist who devours the world by Scott Indirisek, [profile of Katherine Bernhardt, GQ Sept 2019]

“I guess that's my aesthetic,” Bernhardt says, “raw, stained, messy, using-your-hand-in-it art.”

[. . . .]

But when it comes to her own practice, Bernhardt is reserved, if not mildly uncomfortable. She seems uninterested in unpacking the hows and whys of her paintings: the meaning of an oversized Star Wars stormtrooper, her thoughts on Jerry Saltz dubbing her a “female bad-boy painter.” It seems enough that Bernhardt has made these things, launched them out into the world, let them speak in their own self-assured, proudly doofy way. She'd rather bitch about the way crypto-bros have driven up rents in San Juan, or tell me about how obsessed she is with the emo rapper Juice WRLD (Shout your name in hills in the valley, goes her current favorite track, “Desire.” Whole world's gonna know you love me.) And while she does read her own reviews, Bernhardt puts more faith in a different audience. Recently she had a solo show at upstate New York's Art Omi—Pink Panthers posing with cigarettes, Scotch-tape rolls, clusters of bananas—and she was psyched to learn that the center's youngest visitors were responding to the work. Classes were being held. A future generation was learning that art can be as weird, scuzzy, and funny as you dare it to be. “When kids like it,” she says, “I know that it's good.”

Getting the World into Poems, by Charles Simic [NYRB 6/25/2010, reviewing Koethe, Armantrout, and T. Hoagland]

Nothing There: The late poetry of John Koethe, Robert Hahn, Kenyon Review, July 2017

Re-read

Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters (title story) By J.D. Salinger Hot, Cold, Heavy Light, by Peter Scheldahl [essay on Beuys, Peter Hujar, profile of Harrison, Whistler]A Sense of Direction, by G. Lewis-Krauss [first two parts] Reading

Whistler, life for art’s sake, Daniel SutherlandThe Silk Roads, Peter FrankopanThe Burning House, by Hanya Yanagihara [paris review website]

A Writer’s Berlin, by Jeffrey Eugenides [food and wine]

The Use of Beautiful Places by Angie Mlinko [FS&G website]

Whole Earth Troubadour by Angie Mlinko [review of W.S. Merwin, NY Review of Books 12/17/2017

The Aesthetics of Enchantment by Rebecca Ariel Port [review of Angie Mlinko Marvelous Things Overhead, LARB 11/10/13]

The questionnaire interviews Angie Mlinko [LARB 3/15/13]

5 days in Tokyo with Justin Theroux by Cam Wolf (GQ, Sept. 2019)

To be read (aspirations in progress)

Zen and Japanese Culture, D.T. Suzuki [Purchased Kawaza Museum in Oct. 2018, been “reading” Since then]Swann’s Way (Davis) [Week One: through page 14]Compare Howard:This teasing inflicted by my great- aunt, the spectacle of my grandmother’s vain entreaties and of her efforts, doomed in advance, to take the liqueur-glass away from my grandfather, were the kind of things you grow used to later in life, to the point of smiling at them and blithely siding with the persecutor deliberately enough to convince yourself that no persecution is involved; but at the time they so horrified me that I wanted to hit my great-aunt. Yet as soon as I would hear “Bathilde, come and stop your husband from drinking cognac!” already a man in my cowardice, I did what we all do, once we have grown up, when we confront suffering and injustice: I chose not to see them.

with Davis:This torture which my great-aunt inflicted on her, the spectacle of my grandmother’s entreaties and of her weakness, defeated in advance, trying uselessly to take the liquer glass away from my grandfather, are the kind of things which you later became so accustomed to seeing that you smile as you contemplate them and take the part of the persecutor resolutely and gaily enough to persuade yourself privately that no persecution is involved; at that time they filled me with such horror that I would have liked to hit my great aunt. But is soon as I heard: “Bathilde, come and stop your husband from drinking cognac!,” already a man in my cowardice, I did what we all do, once we are grown up, when confronted with sufferings and injustices: I did not want to see them;

Old Masters, by Thomas Bernhard [10 pages in, need to start anew]

ἑαυτοῦ ἐπιμελεῖσθαι [but 0101010101010101] [Olivia Long, Lonely City]

“What did I want? What was I looking for? What was I doing there, hour after hour? Contradictory things. I wanted to know what was going on. I wanted to be stimulated. I wanted to be in contact and I wanted to retain my privacy, my private space. I wanted to click and click and click until my synapses exploded, until I was flooded by superfluity. I wanted to hypnotics myself with data, with coloured pixels, to become vacant, to overwhelm any creeping anxious sense of who I actually was, to annihilate my feelings. At the same time I wanted to wake up, to be politically and socially engaged. And then again I wanted to declare my presence, to list my interests and objections, to notify the world that I was still there, thinking with my fingers, even if I’d almost lost the art of speech. I wanted to look and I wanted to be seen, and somehow it was easier to do both via the mediating screen.”

[Lonely City]

The Lonely City, O. Laing - Redux #1

On latest walkabout, I read the Lonely City by Olivia Lang and saw as much ‘80s era downtown scene art as I could. This inevitably involved coming into contact with art about AIDs and artists who succumbed to it. That aspect was humbling, in how little I knew of how bad it was, how much good art came out of it, and how much good art may have been made if more had been done, sooner, without the fear and the stigma and the old-fashioned, regressive fear-mongering strain in society that we presume to have overcome.

(D. Wojnarowicz)

(D. Wojnarowicz)

(The Kleptocracy)

(D. Wojnarowicz)