Omens and Omelettes

Ulysses was censored. That is so 20th Century.

Lonely City (O Lang) - Redux #3, Art's Integrating Function

Lang again:

It’s a funny business, threading things together, tying them and patching them with cotton or string. Practical, but also symbolic, a work of the hands and the psyche itself. One of the most thoughtful accounts of the meanings contained in activities of this kind is provided by psychoanalyst and pediatrician D.W. Winnicott, an heir to the work of Melanie Klein. Winnicott began his psychoanalytic career treating evacuee children during the Second World War. He worked lifelong on attachment and separation, developing along the way the concept of the transitional object, of holding, and of false and real selves, and how they develop in response to environments of danger of safety.

In Playing and Reality, he describes the case of a small boy whose mother repeatedly left him to go into hospital, first to have his baby sister and then to receive treatment for depression. In the wake of these experiences, the boy became obsessed with string, using it to tie the furniture in the house together, knotting tables to chairs, yoking cushions to the fireplace. On one alarming occasion, he even tied a string around the neck of his infant sister.

Winnicott thought these actions were not, as the parents feared, random, naughty, or insane, but rather declarative, a way of communicating something inadmissible in language period. He thought that what the boy was trying to express was both a terror of separation and his desire to regain the contact he experienced as imperiled, maybe lost for good. “String,” Winnicott wrote, “can be looked upon as an extension of all other techniques of communication. String joins, just as it also helps in the wrapping up of objects and in the holding of unintegrated material. In this respect string has a symbolic meaning for everyone,” adding warningly, “an exaggeration of the use of string can easily belong to the beginning of a sense of insecurity or the idea of a lack of communication.”

The fear of separation is a central tenet of winnicott's work. Primarily an infantile experience, it is a horror that lives on in the older child and the adult, returning forcibly in circumstances of vulnerability or isolation. At its most extreme, the state gives rise to the cataclysmic feelings he called fruits of privation, which include:

1. going to pieces

2. falling forever

3. complete isolation because of there being no means for communication

4. Disunion of psyche and Soma.

This list reports from the heart of loneliness, its central court. Falling apart, falling forever, never resuming vitality, becoming locked in perpetuity into the cell of solitary confinement, in which a sense of reality, of boundedness, is rapidly eroded: these are the consequence of separation, its bitter fruit.

What the infant desires in these scenes of abandonment is to be held, to be contained, to be soothed by the rhythms of the breath, the pumping heart, to be received back through the good mirror of the mother’s smiling face.

As for the older child comma or the adult who is in adequately nurtured or has been cast backwards by loss into a primal experience of separation, these feelings often spark a need for transitional objects, cathected with love, things that can help the self to gather and regroup.

[ . . . ]

According to Winnicott, this kind of activity – [playing with string] – could do more than simply deny separation or displace feeling. The use of transitional objects like string would also be a way of acknowledging damage and healing wounds, binding up the self so that contact could be renewed. Art Winnicott thought, was a place in which this kind of labor might be attempted, where one could move freely between integration and disintegration, doing the work of mending, the work of grief, preparing oneself for the dangerous, lovely business of intimacy.

INPUT RE: 9/1-9/8, 2019

Read or finished:

33 Artists in 3 Acts by Sarah ThorntonThe Lonely City by Olivia LaingJohn Currin articles:a. John Currin, Painting’s Male Provocateur, Turns his Brush to Men [GQ Sept 2019]

b. Irresistible, by Peter Schjeldahl [12/7/2003, New Yorker]

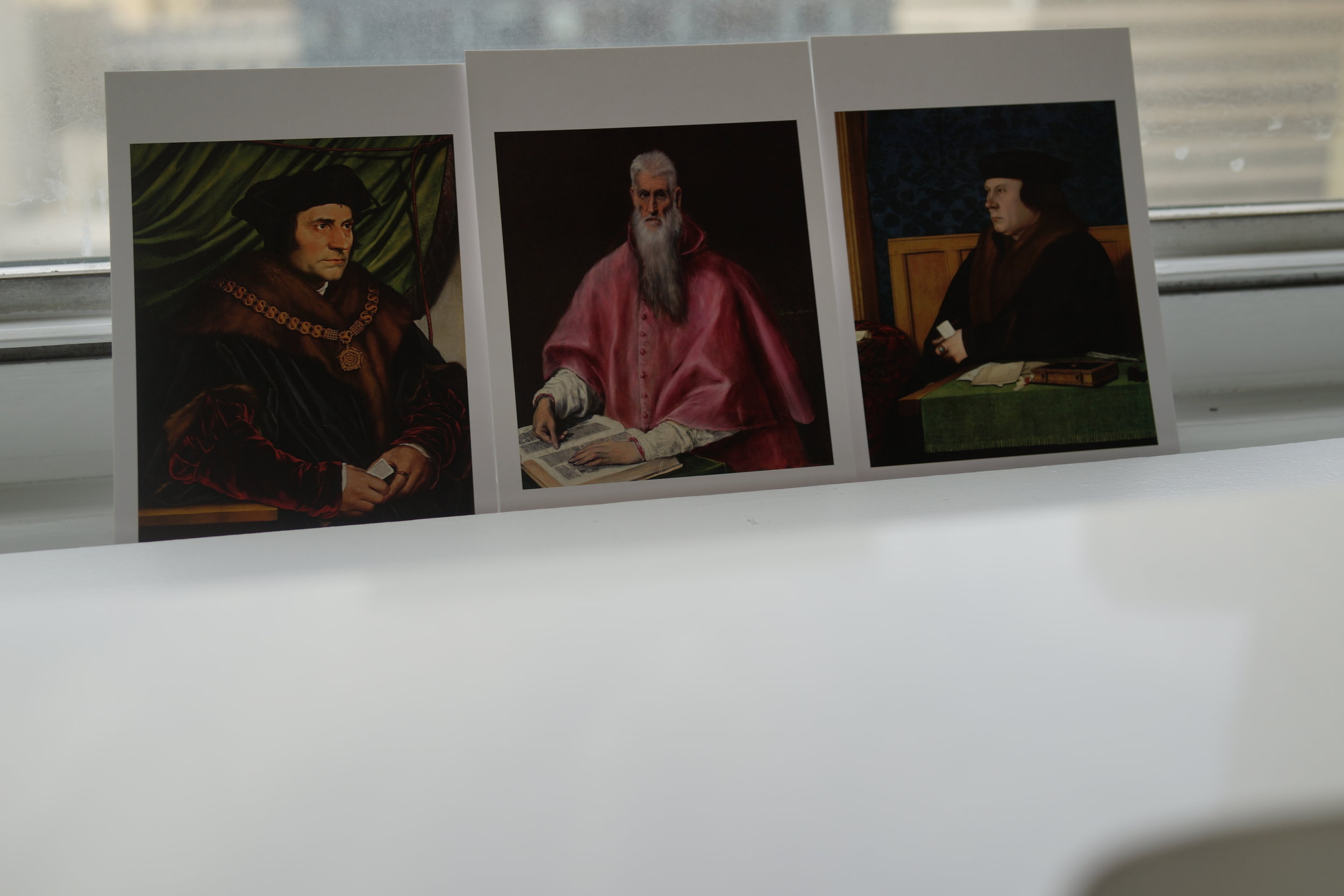

I assumed that Currin’s skilled, sly, ineffably old-fashioned work—pastiches of Old Masters and hack illustration, in easel paintings fit for a bygone Beaux-Arts salon—would remain a renegade taste, marginal to video, photography, installations, and other dominant, paint-allergic modes of contemporary art.

But to resist Currin’s claim to preëminence in art’s present state and near-future course suddenly seems beyond anyone’s ability.

[. . . .]

You wouldn’t think that resourceful, unremitting, honed offensiveness would be a winning artistic strategy. By rights, Currin’s radical conservatism ought to disgust art-world cognoscenti, and conservatives should abhor his poisoned-sugar erotica. So what’s up?

I hazard that in Currin’s art manifold pleasure disarms revulsion—without eliminating it. He demonstrates the power of the aesthetic to overrule our normal taste, morality, and intellectual convictions.

[. . . . /close of article/]

He announces a situation in which artists, wielding art, trump critics who enforce ideas. If his paintings are to be effectively countered, it must be by other, newer, better paintings.

c. Lifting the Veil by Calvin Tompkins [New Yorker profile 1/21/2008]

[the lede]

The painting shows three young women standing close together in a room. The woman in the middle faces us directly, head held high; her dress is falling open, and her bra has been pulled down to expose both breasts. On either side of her, the other two—one nude, one wearing a chic cocktail dress unzipped in back—touch her erotically. The canvas is eighty-eight inches high by sixty-eight wide. It has the scale and pyramidal structure of a Renaissance altarpiece, but, according to John Currin, who began work on it four days ago, the immediate source was an Internet porn site. What struck him about the image, he explains, was “this completely archaic pose, like the three witches or something. I think of them as Danish, because of the thinning blond hair and the gaps between the teeth. They’re not pretty enough to be Swedes. Oh, and I want to do a still-life down there in the lower right corner. I don’t really know where this picture is going yet, but I think it’s going to work.”

[ . . . . /A complication; rising action/]

A reason presented itself soon enough, in the headlines about riots in the Islamic world over twelve Danish newspaper cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad. “The response to that totally shocked me,” Currin said at dinner that night. “That the Times decided that it was not going to show the cartoons—O.K., they’re terrible-ass cartoons from a quality standpoint, but the idea that those thugs get offended and we just acquiesce, that was the most astonishing display of cowardice. And also the killing of Theo van Gogh, the film director, by some jihadist in Amsterdam—all of a sudden the most liberal societies in the world were having intimidation murders happen. That’s when it occurred to me that we might lose this thing—not the Iraq war but the larger struggle.” When I asked how this tied into his making pornographic paintings, Currin talked about low birth rates in Europe, and people having sex without having babies, and pornography as a kind of elegy to liberal culture, at which point I lost the thread. “I know how right wing this sounds,” I recall him saying, “but I was thinking how pornography could be a superstitious offering to the gods of a dying race.”

[. . . ./ the closing grafs/]

A week before Christmas, the painting suddenly came together. The body of the right-hand figure, indistinct until now, looked fully three-dimensional, with luscious flesh tones and a sensuous play of light and shadow on her belly. Currin had sketched in grisaille a still-life of bone-china cups and plates at the lower right, and he had turned the bed behind the three figures into a distinct presence, with a rumpled sheet and a curvy leg copied from his and Rachel’s flamboyantly rococo bed at home. Right now, he planned to concentrate on the three figures. “There’s not enough depth in them,” he said. The painting, he said, would not be in his upcoming show in London. Larry Gagosian had told me earlier that he would like to have this one himself—something dealers are inclined to say when they want to establish a record price.

Currin had agreed sometime earlier, rather reluctantly, to let me watch him paint, but somehow this had not happened. Today it did. He set up a palette, choosing three tubes of Robert Doak oil paint from a worktable piled high with several dozen others, and squeezing out small dollops from each. The colors were yellow ochre, vermillion, and Turkey umber, which registers as blackish green. From a lineup of liquid mediums in glass bottles, each of which had a different consistency and drying time, he selected a mixture of stand oil and balsam and poured a little of it into a small cup that was affixed to the palette. “And here’s the white I’m so excited about,” he said, squeezing from a larger tube of lead white. He went to work right away, dabbing a rather large bristle brush first into the white, and then the umber and the other two colors, mixing them quickly with a little of the oil medium on the palette, remixing until he had the brownish tone he was after, and then applying it to the leg of the central figure with quick, deft strokes. He walked back ten or twelve paces, looking, then added more vermillion and went over the section again, making it darker at the outside edge of the leg and lighter toward the middle.

I was surprised to see how fast he worked. After about ten minutes, the brownish pigment, applied over the white ground, had made its magical transition into live flesh. “I have about an hour before it gets sticky and becomes unworkable,” he explained. Now and then, he used his index finger to blur or blend the paint. “Say I want a sort of purply knee, slightly bruised or something,” he said. “I go in with black and red, maybe a little yellow.” He did so. He switched to a sable brush, much softer than the one he had been using, to work around the knee. “It starts to multiply, the grading of tones, until it becomes thousands of tones,” he reflected. “Some are accidental and some are intentional. It’s great when the accidental becomes indistinguishable from the intentional. That’s when it begins to seem like a living thing.” Watching him, it occurred to me that every brushstroke, every gradation in tone reflected a body of knowledge and a capacity for intuitive decisions that reached backward and forward in time. Also, that the art of figurative painting, which has been around for twenty thousand years or so, retains enough challenges to keep us enthralled for an additional millennium or two.

Currin stood back to look at what he’d done, then picked up a soft cloth and began wiping it off. The central figure’s legs, he said, would eventually be sheathed in green stockings. He had just been showing me how he worked.

The demonstration made me think of three other things he had said during our talks:

“The meaning of the painting is what you do with your hands.”

“The way things are painted trumps everything else.”

“So much art now doesn’t want to look like art, but painting can’t help it.”

The artist who devours the world by Scott Indirisek, [profile of Katherine Bernhardt, GQ Sept 2019]

“I guess that's my aesthetic,” Bernhardt says, “raw, stained, messy, using-your-hand-in-it art.”

[. . . .]

But when it comes to her own practice, Bernhardt is reserved, if not mildly uncomfortable. She seems uninterested in unpacking the hows and whys of her paintings: the meaning of an oversized Star Wars stormtrooper, her thoughts on Jerry Saltz dubbing her a “female bad-boy painter.” It seems enough that Bernhardt has made these things, launched them out into the world, let them speak in their own self-assured, proudly doofy way. She'd rather bitch about the way crypto-bros have driven up rents in San Juan, or tell me about how obsessed she is with the emo rapper Juice WRLD (Shout your name in hills in the valley, goes her current favorite track, “Desire.” Whole world's gonna know you love me.) And while she does read her own reviews, Bernhardt puts more faith in a different audience. Recently she had a solo show at upstate New York's Art Omi—Pink Panthers posing with cigarettes, Scotch-tape rolls, clusters of bananas—and she was psyched to learn that the center's youngest visitors were responding to the work. Classes were being held. A future generation was learning that art can be as weird, scuzzy, and funny as you dare it to be. “When kids like it,” she says, “I know that it's good.”

Getting the World into Poems, by Charles Simic [NYRB 6/25/2010, reviewing Koethe, Armantrout, and T. Hoagland]

Nothing There: The late poetry of John Koethe, Robert Hahn, Kenyon Review, July 2017

Re-read

Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters (title story) By J.D. Salinger Hot, Cold, Heavy Light, by Peter Scheldahl [essay on Beuys, Peter Hujar, profile of Harrison, Whistler]A Sense of Direction, by G. Lewis-Krauss [first two parts] Reading

Whistler, life for art’s sake, Daniel SutherlandThe Silk Roads, Peter FrankopanThe Burning House, by Hanya Yanagihara [paris review website]

A Writer’s Berlin, by Jeffrey Eugenides [food and wine]

The Use of Beautiful Places by Angie Mlinko [FS&G website]

Whole Earth Troubadour by Angie Mlinko [review of W.S. Merwin, NY Review of Books 12/17/2017

The Aesthetics of Enchantment by Rebecca Ariel Port [review of Angie Mlinko Marvelous Things Overhead, LARB 11/10/13]

The questionnaire interviews Angie Mlinko [LARB 3/15/13]

5 days in Tokyo with Justin Theroux by Cam Wolf (GQ, Sept. 2019)

To be read (aspirations in progress)

Zen and Japanese Culture, D.T. Suzuki [Purchased Kawaza Museum in Oct. 2018, been “reading” Since then]Swann’s Way (Davis) [Week One: through page 14]Compare Howard:This teasing inflicted by my great- aunt, the spectacle of my grandmother’s vain entreaties and of her efforts, doomed in advance, to take the liqueur-glass away from my grandfather, were the kind of things you grow used to later in life, to the point of smiling at them and blithely siding with the persecutor deliberately enough to convince yourself that no persecution is involved; but at the time they so horrified me that I wanted to hit my great-aunt. Yet as soon as I would hear “Bathilde, come and stop your husband from drinking cognac!” already a man in my cowardice, I did what we all do, once we have grown up, when we confront suffering and injustice: I chose not to see them.

with Davis:This torture which my great-aunt inflicted on her, the spectacle of my grandmother’s entreaties and of her weakness, defeated in advance, trying uselessly to take the liquer glass away from my grandfather, are the kind of things which you later became so accustomed to seeing that you smile as you contemplate them and take the part of the persecutor resolutely and gaily enough to persuade yourself privately that no persecution is involved; at that time they filled me with such horror that I would have liked to hit my great aunt. But is soon as I heard: “Bathilde, come and stop your husband from drinking cognac!,” already a man in my cowardice, I did what we all do, once we are grown up, when confronted with sufferings and injustices: I did not want to see them;

Old Masters, by Thomas Bernhard [10 pages in, need to start anew]

ἑαυτοῦ ἐπιμελεῖσθαι [but 0101010101010101] [Olivia Long, Lonely City]

“What did I want? What was I looking for? What was I doing there, hour after hour? Contradictory things. I wanted to know what was going on. I wanted to be stimulated. I wanted to be in contact and I wanted to retain my privacy, my private space. I wanted to click and click and click until my synapses exploded, until I was flooded by superfluity. I wanted to hypnotics myself with data, with coloured pixels, to become vacant, to overwhelm any creeping anxious sense of who I actually was, to annihilate my feelings. At the same time I wanted to wake up, to be politically and socially engaged. And then again I wanted to declare my presence, to list my interests and objections, to notify the world that I was still there, thinking with my fingers, even if I’d almost lost the art of speech. I wanted to look and I wanted to be seen, and somehow it was easier to do both via the mediating screen.”

[Lonely City]

The Lonely City, O. Laing - Redux #1

On latest walkabout, I read the Lonely City by Olivia Lang and saw as much ‘80s era downtown scene art as I could. This inevitably involved coming into contact with art about AIDs and artists who succumbed to it. That aspect was humbling, in how little I knew of how bad it was, how much good art came out of it, and how much good art may have been made if more had been done, sooner, without the fear and the stigma and the old-fashioned, regressive fear-mongering strain in society that we presume to have overcome.

(D. Wojnarowicz)

(D. Wojnarowicz)

(The Kleptocracy)

(D. Wojnarowicz)

Delillo Deadens, for which I Worship Him: or (As between the apostles Mark and Luke, with whom do you most identify?)

Common place book

On the plane:

Confession, Redemption, and Death: Liu Xiaobo and the Protest Movement of 1989 by Geremie Barme’

One Decent Man by Geremie R. Barme’ (reviewing Simon Leys: Navigator Between Worlds by Philippe Paquet)

I’m so Ronrey by Geremie R. Barme’, The China Journal, January 2006)

New Yorker artist story, female painter age 80 with disorderly cat, descriptions of men dated or loved in the past and food cooked in the present.

In cabs:

The Book: On the Taboo Against Knowing Who You are by Alan W. Watts

The Lonely City Olivia Wang

Qiu ZhiJie

The Old Masters, Thomas Bernard

The constabulary walls, to and fro

But that’s all just ex post facto guilt masking as self-concern. Here we go.

Obsidian flakes glitter, the clear sound of a shovel full of dirt landing and scattering

Over a freshly taken shit.

Moments later, amidst stream gurgle and tree sway,

One foot placed in front of the other

Plastic grocery bag holding raisins &

Peanut butter & banana sandwiches a pendulum

Swinging against the pack in

Placid rhythm. Sunny now. Hail will

Come soon I bet.

Ocelots are real

Maybe it should demand more, cost more, extract more to be able to put oneself in touch w/ one’s past. Maybe in ease, we gain in quickness to the same degree we lose in depth/necessity.

Whim on the top of every door

What if I started to make sense in this calamity - real penetrating insight that extends beyond the particular bounds of my subjective experience - and all of a sudden when it gets (subjectively) better I lose that projecting power?

It seems almost destined to be that way, in the capital “R” Romantic way, as though alleviating suffering (and believe me I say that with one eyed wink) lessens the chances of having said a thing that penetrates?

The Summer of Our Discontent

Transformed, the summer of our discontent is an oasis within which discomfort shoves aside inertia and says the red-wine sea does the moon’s bidding. True and real = trill.

Is it apparent yet that farce is not always the operative mode?

PRESENT COMPANY EXCLUDED IN EVERY WAY,

DANCE YOURSELF CLEAN

Two footprints in the sand

A theory of transference:

Grief and rage—you need to contain that, to put a frame around it, where it can play itself out without you or your kin having to die. There is a theory that watching unbearable stories about other people lost in grief and rage is good for you—may cleanse you of darkness. Do you want to go down to the pits of yourself all alone? Not much. What if an actor could do it for you? Isn’t that why they are called actors? They act for you.

A theory of causation:

Why does tragedy exist? Because you are full of rage. Why are you full of rage? Because you are full of grief.

A theory of aesthetic consumption as an ethical, but radically relative act:

The purpose of art was sympathetic consolation: by recognizing one’s own unhappiness in fiction, one could, if not abolish one’s unhappiness (everyone was inherently and irrevocably unhappy), nonetheless alleviate it to a certain degree. So art, since it reduced the net amount of universal pain, was fundamentally ethical—as with “politics,” “aesthetics” were entirely replaced, or nullified, or superseded, by ethics. Just as questions of political validity depended entirely on the individual actor, questions of aesthetic quality depended entirely on the individual reader: if some communication sympathetically consoled a person, that communication was art—to that person. It was entirely possible that that thing would not be art to another person. There was no abstract standard of “good” or “bad” art that could reconcile disparate opinions. The disparity could be registered, but that, it seemed, was all that could be done.

A borrowed theory on what it might be like to reach the tether’s end:

A month passed in the ward, while nothing happened – not nothing, only flickerings. “Green conductive gel dried on my forehead. Weeping.”

A theory of the ineluctable absurd:

We (royal We) appreciate the yearning for a world that bends toward justice. And it seems plausible that in the flotsam and jetsam of discarded narratives – the scripts, drafts, deleted files and so on – there exists some version of a story that does in fact redeem and give expression to this yearning in a way that hasn’t yet reached the reader’s eyes and lodged itself in her soul, but which might, someday. It need not be a politician’s speech, in other words, though there is that, too, and it might need not to need to be edifying, either.

But increasingly it seems that realism demands an arc that bends toward absurdity. Toward a life lived in a vacuum of ultimate meaning, stretching well beyond the effort to set one’s sights on a particular credo and instead to see what can be done with the available degrees of freedom that are opened up or made manifest and to do so with joy and ebullience.

Stories that end with an ex-mayor of a municipality, tied to four cars with 30-lb test fishing line that are about to drive off in four different directions. Stories in which a man wakes up to become a bug – not like a bug, but the real deal – and has to decide from there what might be done to get through the day. Stories about what 100 people said about Delores, including Superman. Stories about an Uzbek spy stuck in a minaret with his mother-in-law, hoping against hope that the concatenation of drones he stole from the Arbiter and tied together with baling twine will carry them both outside the blast radius, even as he contemplates knocking her out and leaving on his own. Stories incandescent enough to lead to a fatwa or a stoning, lest the storyteller’s imagination be set loose and remake the world.

A theory of perspective:

Homer talks about how people are situated in time. He says they have their backs to the future, facing the past. If you have your face to the past, you just look at the stuff that's already there and take what you need. It's not the same as us, facing the future, where we have to think about that [points behind] then turn around and get it and bring it here, bring it in front of us.

A theory of the American project:

A people who conceive life to be the pursuit of happiness must be chronically unhappy.

ἑαυτοῦ ἐπιμελεῖσθαι

Maybe money really is the last obscenity and we’re so used to handling it, it never occurs to us to wash.

William Gaddis letter to Cynthia Buckman, 1978

Business art is the step that comes after Art. I started as a commercial artist, and I want to finish as a business artist. After I did the thing called ‘art’ or whatever it’s called, I went into business art. I wanted to be an Art Business man or a Business Artist. Being good in business is the most fascinating kind of art. During the hippie era, people put down the idea of business – they’d say ‘money is bad’ and ‘working is bad’ but making money is art and working is art and good business is the best art.

Andy Warhol, the Philosophy of Andy Warhol

The horror is not that art is over-valued but that, deep down, money is worthless.

Peter Schjeldahl

Largely hidden from public view, an ecosystem of service providers has blossomed as Wall Street-style investors and other new buyers have entered the market. These service companies, profiting on the heavy volume of deals while helping more deals take place, include not only art handlers and advisers but also tech start-ups like ArtRank. A sort of Jim Cramer for the fine arts, ArtRank uses an algorithm to place emerging artists into buckets including “buy now,” “sell now” and “liquidate.” Carlos Rivera, co-founder and public face of the company, says that the algorithm, which uses online trends as well as an old-fashioned network of about 40 art professionals around the world, was designed by a financial engineer who still works at a hedge fund. The service is limited to 10 clients, each of whom pays $3,500 a quarter for what they hope will be market-beating insights. It’s no surprise that Rivera, 27, who formerly ran a gallery in Los Angeles, is not popular with artists.

William Alden, Art for Money’s Sake, N.Y. Times, Feb. 3, 2015.

FROM Vincent van Gogh to Henri Rousseau, artists have a long and honourable tradition of dying penniless. Their modern counterparts would rather not. This week MutualArt, a New York-based group of academics and museum experts, announced the start of the first-ever pension trust for visual artists. There is a twist: the contributions of those invited to join the scheme will be in the form of paintings and sculptures—20 works over 20 years. Their sale is supposed to provide each artist with three decades of retirement payouts.

Art for Money’s Sake, The Economist, May 27, 2004.

Value (a Profile of J.S.G. Boggs)

J.S.G. Boggs is a young artist who likes to invite you out to dinner at a restaurant, run up a tab of, say, eighty-seven dollars, and then, while sipping coffee, reach into his satchel and pull out a drawing he’s been working on for several days. The drawing, on a small sheet of high-quality paper, might consist, in this instance, of a virtually exact rendition of the ace side of a hundred-dollar bill. He next pulls out from his satchel a couple of precision pens – one green ink, the other black – and proceeds to apply the finishing touches to his drawing. This activity invariably causes a sti. Guests at neighboring tables crane their necks. Passing waiters stop to gawk. The maitre d’ eventually drifts over, stares for awhile, and then remarks on the excellence of the young man’s art. “Thank you,” Boggs says. “I’m glad you like this drawing, because I intend to use it as payment for our meal.”

At that moment, invariably, a chill descends upon the room. The maître d’ blanches. You can just see his mind reeling (“Oh, no, not another nut case”) as he begins to plot strategy: Should he call the police? How is he going to avoid a scene? But Boggs almost immediately reestablishes a measure of equilibrium by reaching into his satchel and pulling out a real hundred-dollar bill – indeed, the very model for the drawing – and saying, “I mean, of course, if you want, you can take this regular hundred-dollar bill here instead.” Color is returning to the maître d’s face. “but, as you can see,” Boggs continues, “I’m an artist, and I drew this. It took me many hours to do it, and it’s certainly worth something. I’m assigning it an arbitrary price, which just happens to coincide with its face value – one hundred dollars. That means that if you do decide to accept it as full payment for our meal, you’re going to have to give me thirteen dollars in change. So you have to make up your mind whether you think this piece of art is worth more or less than this regular one-hundred-dollar bill. It’s entirely up to you.” Boggs smiles, and the maître d’ blanches once again, because he’s into vertigo: the free-fall of worth and value.

[. . . .]

As far as boogs is concerned, the actual drawings should be considered merely as small parts- the catalysts, as it were- of his true art, which consists of the transactions that they provoke. Thus, in each instance the framed drawing of the money itself was surrounded by several other framed objects, including the receipt, the change (each bill signed and dated by Boggs, each coin scratched

with Boggs' initials), and perhaps some other traces of the transaction (for example, evidence of the item purchased-the cardboard carton from a six-pack of beer; the ticket stubs for an air flight; a neatly pressed set of dress shirts- or a photograph of Boggs actually handing an impeccable waiter his drawing and receiving his change: the very change preserved behind glass in an adjoining frame).

Of course, the fact that all these pieces had now been gathered together, some as loans from private collections and others as entities available for purchase, raised some further questions about the transactions. If, for instance, Boggs did in fact manage to purchase a ticket for a flight from Zurich to London on British Airways – a ticket worth two hundred and ninety Swiss francs – with a drawing

of three overlapping Swiss hundred franc notes, it was easy to see how the ten Swiss francs in change and the actual ticket stub had made it into this show. But how had the initial drawing- which Boggs had presumably "spent" to acquire the other items managed to rejoin them, so that the entire transaction could now be offered for sale, for fifteen hundred dollars? Luckily, as often as not last August

Boggs was right there in the gallery [where his work was shown], eager to respond to any such questions. He seemed to feel that the show itself was a continuation of the series of

transactions that had always begun with his taking pen to paper, and that there was still plenty of occasion for perplexity, confoundment, and revelation.

[ . . . .}

[THE RULES]

[Boggs says] "There are a lot of collectors, in Europe but also here, who want to buy my drawings of currency, but I refuse to sell them- that's the first of my rules.”

This is my Rule No. 2- I will only spend them; that is, go out and find people who will accept them at face value, in transactions that must include a receipt and change in real money. My third rule is that for the next twenty-four hours I will not tell anyone where I've spent that drawing: I want the person who got it to be able to have some time, unbothered, to think about what's just happened.

After that, however- and this is my Rule No. 4- if there is a collector who I know has expressed interest in that sort of drawing I will get in touch with him and offer to sell him the receipt and the change, for a given price. It depends, but for the change and the receipt from a hundred-dollar dinner transaction, for example, the collector might have to pay me about five hundred dollars. The receipt should provide

enough clues to enable the collector to track down the owner of the hundred-dollar drawing, but if the collector desires further clues- the name of the waiter, for example, or his telephone number-I'm always prepared to provide those details, for a further fee. After that, the collector is in a position to get in touch with the drawing's owner and try to negotiate some sort of deal on his own to complete the work."

[ . . . .]

[ON THE AESTHETICS OF MONEY]

At a nearby café, where Boggs and I continued our conversation, he said, “I hope you don’t think I’m doing all this as some sort of insult to money-as if I were putting money down, or something. I think money is beautiful stuff."

I laughed.

"I'm serious." He extracted a dollar bill from his wallet. "I mean, look at this thing. No one ever stops to look at the bills in his pocket - stops and admires the detailing, the conception, the technique. My work is intended partly to get people to look at such things once again, or maybe for the first time. Take this one here. This is an absolutely splendid intaglio print. It's actually the result of three separate printing processes-two on the face side, another on the back-all done on excellent paper. Over the years, because of the danger of counterfeiting, these bills have had to be made more and more intricate, in terms of both imagery and technique. But as far as I'm concerned money is more beautiful and highly developed and aesthetically satisfying than the print works of all but a few modern artists. And a dollar bill is a print: it's a unique, numbered edition. And that's just talking about technique. Now look at the content, the iconography, the history.

That crazy rococo profusion of leaves and scrollwork, symbolizing prosperity. The eagle, with his thirteen arrows in one claw, for the first thirteen states, and the olive branch in the other and, on the olive branch, the olives! And then the other half of the Great Seal, with that strange Masonic pyramid - an unfinished pyramid, still in the process of being built. George Washington, on the facing side of the bill, was a Mason. There's so incredibly much American cultural history wrapped up in this little chit of paper. And it's the same with other currencies."

Boggs paused for a moment, continuing to gaze at his dollar. "'In God we trust,' " he said. "Did you knowthat that phrase wasn't always part of our currency? They started putting it on during the nineteen-thirties, as they withdrew the dollar's gold backing. It used to be you could redeem a ten-dollar bill for ten dollars in gold. In fact, originally dollars were coins. Some of the early American bills included engravings on the back depicting the coins for which the bills could at any moment be redeemed. But when they started withdrawing the dollar's metal backing- when you couldn't redeem your dollars for gold, and, in fact, were no longer allowed even to possess gold on your own except as jewelry-that's when they started putting that phrase on the currency. When you could no longer trust in gold, they invited you to trust in God. It was like a Freudian slip."

- Lawrence Weschler